Battling for the Elements: Rare Earths and Critical Minerals in U.S.-China Competition

Rare earth elements (REEs) like neodymium, dysprosium, and praseodymium, for example, are essential for powerful permanent magnets used in wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, and precision-guided munitions.

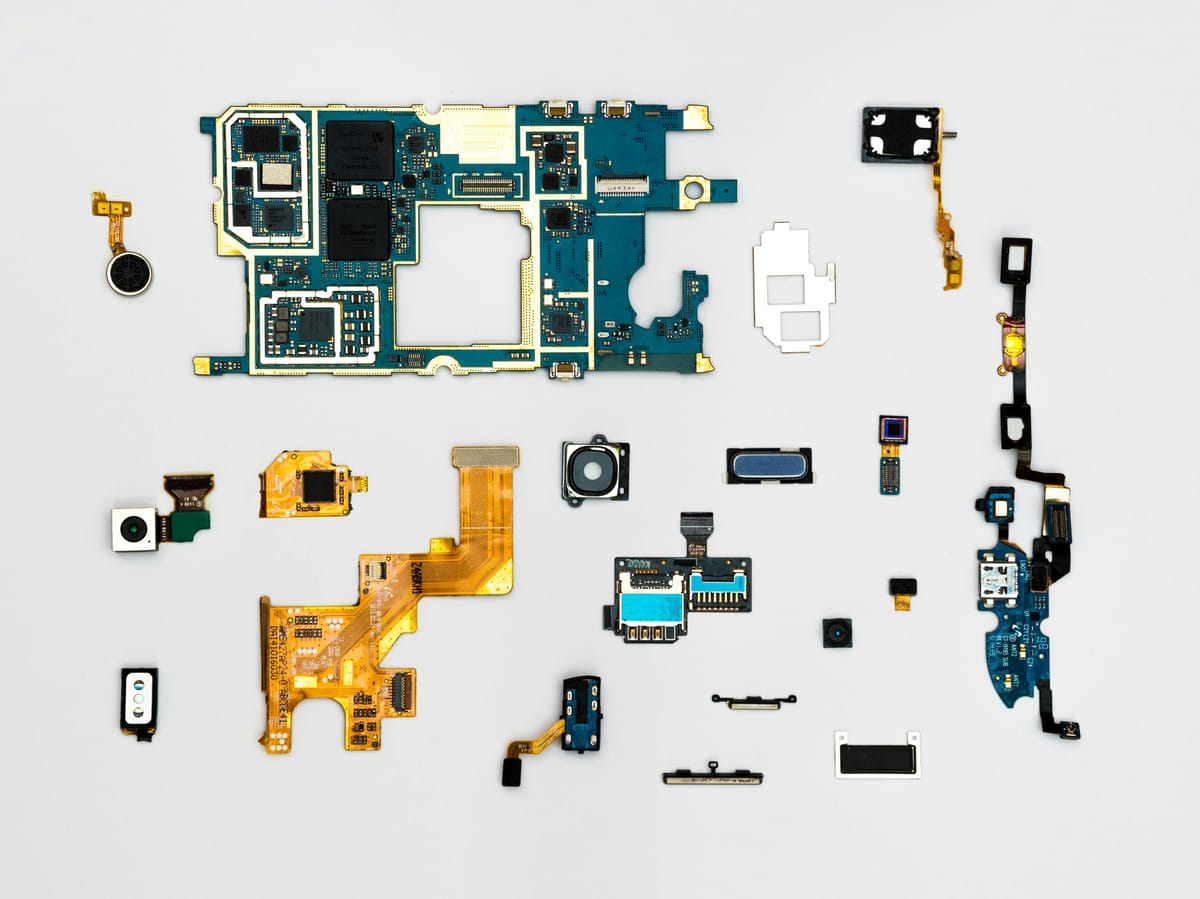

Summary: You can’t build a smartphone, an electric vehicle, or a missile without the right minerals, and right now, China dominates the supply of many critical elements that modern technology runs on. Rare earth elements and other strategic minerals have quietly become a flashpoint in the U.S.-China tech war. Why? Because control over these raw materials translates to control over the supply chains for batteries, chips, weapons systems, and more. In this article, we explore the high-stakes contest over rare earths and critical minerals: how China secured a commanding position, how the U.S. is scrambling to catch up by developing its own sources, and what this “battle for the periodic table” means for the future of tech and geopolitics.

Why Minerals Matter: The Tech Underpinnings

Modern technologies require a vast array of elements, far beyond the silicon and copper that most people think of. Many of these are classified as critical minerals due to their importance and the risk of supply disruption. Rare earth elements (REEs) like neodymium, dysprosium, and praseodymium, for example, are essential for powerful permanent magnets used in wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, and precision-guided munitions. If you want a high-performance electric car or a state-of-the-art fighter jet, you need rare earth magnets. Similarly, other obscure-sounding elements have outsized roles: gallium is used in semiconductor chips and LEDs; germanium is key for fiber optic communications and night-vision systems; cobalt and lithium are indispensable for rechargeable batteries; bismuth finds use in medical and nuclear applications (and emerging quantum tech); even industrial chemicals like bromine are crucial for energy storage and specialty materials.

The catch is that China has become the dominant source or processor for many of these materials, often to an extreme degree. Over decades, China invested in mining and refining and was willing to bear the environmental costs that led others to exit the business. At one point, China was responsible for refining an estimated 80-90% of global rare earth oxides. It also produces the majority of certain byproduct metals like gallium (extracted from aluminum ore) and germanium (from zinc ore). In some cases, China holds near-monopolies; for instance, producing the lion’s share of the world’s magnesium and tungsten. This dominance means that the United States (and many other nations) are heavily reliant on China for critical raw materials that fuel their tech industries and defense sector.

China’s Leverage and “Resource Weaponization”

Beijing understood early on that controlling raw materials could be as strategically powerful as dominating finished tech products. Chinese state media has even referred to rare earths as a “bargaining chip” in dealings with the West. And indeed, China has not hesitated to weaponize its control when it suits its interests. A famous example came in 2010: during a diplomatic spat with Japan, China suddenly halted rare earth exports to Japan, sending shockwaves through global industries that depended on those minerals. Prices spiked, and manufacturers worldwide woke up to the supply risk.

More recently, in mid-2023, as U.S.-China tech tensions escalated, China imposed strict export license requirements on shipments of gallium and germanium, vital for semiconductors and military optics; explicitly in retaliation for U.S. chip sanctions. Chinese officials also hinted at curbing other materials (they mentioned bismuth and even bromine-related compounds) if pressures increase. This tit-for-tat move underscored that China sees strategic minerals as a pressure point in the tech war. It was a shot across the bow signaling that if the U.S. tries to choke off China’s access to advanced tech (chips, AI, etc.), China can retaliate by choking off materials that U.S. industries need.

For the United States, this dependency is untenable long-term. It’s a classic strategic vulnerability: if an adversary can “choke off critical mineral supplies, it could cripple industries.” Imagine U.S. electric vehicle production stalling without lithium or rare earth magnets, or defense manufacturing grinding to a halt without steady supplies of specialty metals. The risk is clear, and recent Chinese actions have only heightened the urgency in Washington to secure a stable, independent supply of these inputs.

America’s Response: Re-shoring, Ally-shoring, and Innovation

Recognizing the threat, the U.S. in the past few years has swung into action to rebuild its critical minerals supply chain. It’s not easy, the capability atrophied after decades of offshoring, but multiple strategies are being pursued in parallel:

- Reopen Domestic Mines and Refining: The U.S. is mapping its own geology to identify viable deposits of rare earths and other critical minerals, and looking to streamline the permitting process for new mines. For example, there are efforts to boost production of rare earth elements from deposits in California and other states. The Energy Act of 2020 and provisions in the Defense Production Act have unlocked funding to support companies in mining and refining these minerals domestically. Mining is just one part; the processing (separating and refining the raw ore into usable high-purity materials) is often the more complex step, and one that China mastered while other countries ceded the dirty work. Now the Pentagon has even invoked wartime powers (DPA Title III) to fund the construction of rare earth separation facilities in the U.S. and in allied countries. The logic is straightforward: if the market won’t immediately support these costly projects, government backing will jump-start them in the name of national security.

- Allied Partnerships: The U.S. is leveraging relationships with resource-rich allies to diversify supply. Australia, for instance, is a major producer of rare earth ores outside of China, and the U.S. has inked partnerships to support Australian mines and set up processing plants (one example is a planned rare earth processing facility in Texas in collaboration with Australia’s Lynas Corp). Similarly, partnerships with countries like Canada, Brazil, and others are being pursued for a range of minerals. The idea is a “friend-shoring” of supply chains, to make sure that if we can’t mine it at home, we’re buying it from trusted friends rather than strategic competitors.

- Innovative Extraction: There’s interesting work on extracting critical elements as byproducts of existing industrial processes. The U.S., for example, has large bauxite (aluminum ore) residue piles that historically weren’t used for anything; now, research is looking at economically extracting gallium from those waste streams, since gallium often exists in trace amounts in bauxite. Another project is to exploit the vast bromine reserves in Arkansas brine pools. Bromine compounds are used in some high-tech materials, and Arkansas’s bromine could feed into making things like chromium sulfide bromide (a new semiconductor material) domestically. These efforts are niche but point to a broader approach: get creative in finding mineral sources that were previously overlooked, and co-locate them with manufacturing. If you build a chip fab next to a bromine source, you secure that link in the chain and reduce shipping vulnerabilities.

- Substitution and Recycling: On the demand side, the U.S. is also encouraging innovation to reduce reliance on scarce materials. For example, researchers are looking for ways to design electric motors that don’t need rare earth magnets, or to find battery chemistries that use less cobalt or no cobalt. This is a long-term play; perhaps new technologies can circumvent the need for the most problematic minerals. Meanwhile, there’s a push for recycling: retrieving rare earths and other critical materials from old electronics, used EV batteries, and other end-of-life products. The Department of Energy has funded projects to develop rare-earth-free magnets and improve recycling methods for elements like lithium and cobalt. Over the next 4-5 years, recycling isn’t going to replace mining, but it could start contributing a small but growing share of supply. Even a modest contribution helps alleviate pressure on the primary supply.

These steps mark a significant policy shift. After the 2010 rare earth embargo scare, there was some effort in the U.S. to respond, but it is in the 2020s, with the broader tech competition heating up, that we see a comprehensive strategy emerging. The National Security Strategy now explicitly highlights ending “threats against our supply chains that risk U.S. access to critical resources, including minerals and rare earth elements” as a priority. In plain terms, that means ensuring U.S. industry and the military are never again at the mercy of a foreign power for essential inputs. It’s part of a doctrine of economic security, protecting the industrial base from external coercion.

The Road Ahead: Cost, Cooperation, and Conflict

Standing up new mines, refineries, and supply chains is not quick. There will likely be bumps in the road. Opening a new mine in the U.S., for example, can take years of permitting (and there may be environmental opposition). Processing facilities involve handling nasty chemicals and waste, raising environmental and community concerns that must be managed. All of this will require balancing strategic urgency with environmental responsibility.

In the short run, as the U.S. and others invest in non-Chinese sources, we could see some market turbulence. Prices for certain minerals might rise because non-Chinese production can be more expensive (China has been the lowest-cost producer, partly by ignoring environmental costs). Indeed, diversifying away from the cheapest supplier often “comes at a cost,” potentially leading to higher prices for manufacturers and consumers. We might also see China reacting economically. It has, in the past, flooded markets with a mineral to crash the price and undercut foreign competitors; a tactic to undermine new mining projects. If, say, the U.S. and Australia start ramping up rare earth production, China might temporarily lower its export prices or increase output to make those projects look uneconomical. Policymakers will have to monitor such dynamics closely.

For the U.S. and its allies, however, the long-term payoff of securing critical minerals is undeniable. It directly addresses a key vulnerability: the risk that China could use resource dominance as a strategic trump card. By 2030, the aim is for the U.S. and partners to have a diversified, secure supply of the essential elements that feed high-tech economies and advanced weapons. Achieving that will “nullify one of China’s quiet but potent advantages” in the geopolitical arena.

There’s also a strong alliance dimension. Initiatives like the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council have critical minerals on the agenda, and the Quad (U.S., Japan, India, Australia) has a working group on rare earth cooperation. This is a recognition that no single country can easily break China’s hold alone, but together, a coalition of democracies can pool resources, share the investment burden, and coordinate research so that supply chains are mutual and robust. For example, one country might focus on mining, another on refining, another on magnet production, ensuring everyone has reliable access. Such burden-sharing spreads the cost and strengthens alliance cohesion around a common goal of not being beholden to Beijing for vital materials.

From China’s perspective, these moves by the West are likely seen as a threat to a leverage point it long took for granted. Chinese commentary sometimes notes that if the U.S. tries to cut off China’s access to high tech, China can retaliate by cutting off minerals. It’s a form of mutually assured economic disruption. In a sense, this minerals contest is part of the broader decoupling story: as the U.S. seeks to “reindustrialize” and source critical inputs from home or allies, China may look to assert its grip or find new consumers for its mineral exports. We might see China tightening partnerships with other nations (for instance, in Africa or South America) through infrastructure and investment deals to secure raw materials for itself as well, a preemptive diversification on its side.

Implications: For industries like automotive, aerospace, renewable energy, and electronics, the reshuffling of mineral supply chains could bring both challenges and opportunities. Companies might face higher input costs in the interim (e.g., non-Chinese rare earths might be pricier), which could trickle down into product prices. They will also need to vet their supply chains for resilience, ensuring they have alternative suppliers for critical materials. On the flip side, businesses in the mining, recycling, and materials processing sectors in the U.S. and allied countries could see a renaissance, buoyed by government support and guaranteed contracts. Regions rich in certain resources (like Australia’s rare earth mines or U.S. states with lithium brines) might experience a mini boom.

Environmentally, the push to mine and process these minerals outside China is a double-edged sword. It’s an opportunity to do so with higher environmental standards, spreading best practices, and reducing the overall damage that occurs when things are concentrated in one jurisdiction with lax rules. However, local communities will rightly demand that these operations be clean and safe. Part of the cost increase is doing it “the right way.”

Zooming out, the competition over rare earths and strategic minerals is fundamentally a battle for the material underpinnings of future technology. Dominance in AI, electrification of transport, renewable energy, and advanced weaponry all rest on a foundation of elements from the Earth’s crust. In the next few years, we will likely see the U.S. and allies literally break new ground, opening mines, building processing plants, to reduce China’s stranglehold in this domain. It will be expensive and complex, but as officials often note, the cost of inaction is higher. Recent events have shown that a single export curb announcement from Beijing can send Western industries scrambling. Thus, even if it means higher costs in the short run, the U.S. appears determined that by 2030 it will no longer be caught flat-footed by a mineral embargo. The supply chains of the future, for EVs, drones, smartphones, and energy systems, should ideally be shielded from geopolitical whims.

In summary, rare earths and critical minerals have moved from a wonky niche topic to center stage in the U.S.-China strategic contest. It’s a reminder that great power competition isn’t just about missiles and markets, but also about mines and materials. By securing the raw ingredients of the tech economy, the U.S. and its partners aim to remove a key leverage point that China currently holds. And in doing so, they not only protect their industries but also send a message: economic coercion cuts both ways, and diversification is the antidote to dependence.

Comments ()