Chips and Geopolitics: Why Semiconductors Are at the Heart of the U.S.-China Tech Rivalry

In response to these vulnerabilities, the United States has launched an ambitious push to “reshore” semiconductor manufacturing; essentially, to bring chip fabs back onto U.S. soil.

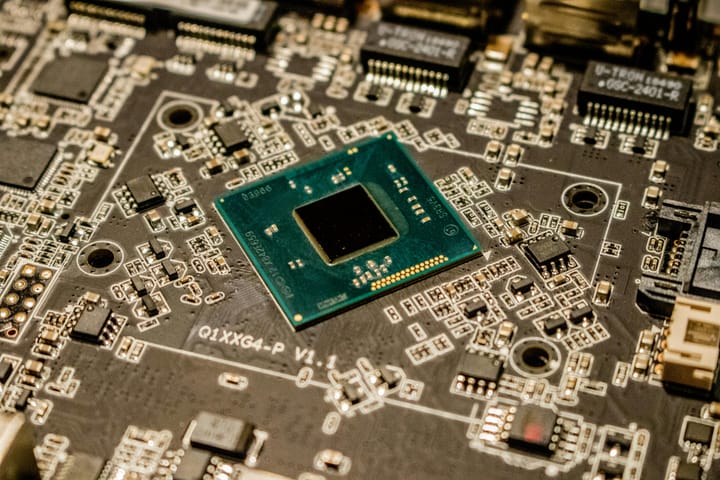

Summary: Tiny silicon chips have outsized importance in the geopolitical chess match between America and China. Semiconductors, the brains in our phones, computers, data centers, and fighter jets, are essential to modern life and military might. For decades, the U.S. led in chip design and innovation, while manufacturing gravitated to Asia. Now, as technology underpins economic strength and national security, both Washington and Beijing see leadership in semiconductors as non-negotiable. This article explores the semiconductor showdown: America’s efforts to rebuild a secure chip supply chain at home and deny China cutting-edge chips, versus China’s campaign for self-sufficiency in a field long dominated by others. The battle for silicon supremacy reveals both countries’ broader strategies, blending innovation, supply chain realignments, and economic statecraft, and carries huge implications for the global economy.

Silicon Backbone, Strategic Vulnerability

Semiconductors are often called the “oil” of the digital era; a foundational resource that powers everything from smartphones to missiles. U.S. dominance in chips has been a pillar of its economic and military strength for years. American firms pioneered microprocessors and specialized chips, and U.S.-allied nations (Taiwan, South Korea, Japan) became manufacturing powerhouses. However, this globalized model also introduced strategic vulnerabilities. The vast majority of the most advanced chips are made in East Asia, notably by Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung. Meanwhile, China is the world’s largest semiconductor consumer and a significant producer of lower-end chips.

This concentration of production abroad means that in a crisis or conflict, the U.S. could face supply disruptions for critical components. Policymakers are especially wary of the dependence on Taiwan, an island whose “dominance of semiconductor production” magnifies its geopolitical importance. A single Taiwanese company (TSMC) produces the majority of the world’s cutting-edge logic chips. Were a military conflict or blockade to befall Taiwan, it could “cut off much of the world’s advanced chip supply, with catastrophic economic consequences,” as one analysis noted. It’s no surprise, then, that securing the semiconductor supply chain has become a national security priority on par with military readiness. The latest U.S. National Security Strategy explicitly frames tech manufacturing independence as vital to security, calling for “reindustrializing our economy” and “controlling our own supply chains and production capacities”.

America’s Chip Reshoring and Tech Denial Strategy

In response to these vulnerabilities, the United States has launched an ambitious push to “reshore” semiconductor manufacturing; essentially, to bring chip fabs back onto U.S. soil. A marquee effort is the $52 billion CHIPS Act (passed in 2022), which provides generous grants, loans, and tax credits to spur domestic semiconductor plants. This has already attracted big projects: for example, TSMC (Taiwan’s chip giant) is investing $40 billion in new advanced fabs in Arizona, the largest foreign direct investment in U.S. microelectronics history. Intel and Samsung are also expanding U.S. fab plans. The overarching goal in the next five years is to establish a foothold of leading-edge chip production onshore, so the U.S. and allies are not entirely dependent on Asia’s foundries.

However, building cutting-edge fabs is an enormously complex undertaking. A state-of-the-art plant for 3-nanometer chips can cost on the order of $15-20 billion, require ultra-specialized equipment, and demand a huge base of skilled workers. The U.S. is finding that money alone doesn’t solve all challenges. Many essential chip manufacturing tools come from abroad; for instance, the only company making extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines (needed for the most advanced chips) is ASML in the Netherlands, and each machine costs about $350 million. Dozens of other critical tools are produced by suppliers in Japan and elsewhere. This means U.S. fab projects still rely on imported equipment, creating potential chokepoints if geopolitical tensions lead those supplier nations to withhold tools. There are also enormous infrastructure needs: fabs consume vast electricity and millions of gallons of ultrapure water per day for manufacturing. U.S. locations often need significant upgrades to power grids, water treatment facilities, and cleanroom space to support a megafab.

The human capital gap is another hurdle. The Arizona TSMC project encountered delays partly due to shortages of skilled construction workers and engineers experienced in advanced fab build-outs. Even with incentives, TSMC had to push back its production timeline because there were “insufficient skilled workers” on-site. Additionally, producing chips in America currently costs 30-50% more than in East Asia due to higher labor and operational costs. All this illustrates that while bringing chip manufacturing home is critical, it won’t be quick or easy.

To mitigate these challenges, the U.S. government is not just throwing money at the problem, but also fostering partnerships and policy tweaks. Incentives like investment tax credits aim to offset cost disadvantages. Joint ventures are being encouraged so that U.S. firms can team up with foreign equipment makers and experienced chip manufacturers to jump-start domestic fabs. There’s also a focus on building out the supporting ecosystem, from training chip engineers to ensuring reliable supplies of chemicals, silicon wafers, and other inputs. Over the next few years, the U.S. hopes to at least establish a baseline domestic capacity for high-end chipmaking, both as an economic boost and as a hedge against worst-case scenarios (like a disruption in the Taiwan Strait).

While America ramps up its own production, it is simultaneously tightening the screws on China’s access to advanced chips. Since 2018, successive U.S. administrations have ratcheted up export controls on semiconductor technology to China. This effort culminated in sweeping rules in 2022-2023, effectively banning the sale of cutting-edge GPU accelerators and restricting semiconductor equipment exports to China. The aim is clear: slow China’s progress in the highest-performance chips, especially those used for AI and supercomputing (which have military applications). U.S. allies like the Netherlands and Japan have aligned with these export controls to deny China the tools for making sub-10nm chips. These measures have “bought time, but not much,” as China is aggressively mobilizing to replace foreign technology and achieve self-reliance. Beijing has poured over $150 billion into its national semiconductor initiative, building dozens of new fabs and developing an indigenous supply chain for equipment and materials.

Indeed, China’s progress should not be underestimated. In 2022, its leading chip foundry, SMIC, reportedly succeeded in producing 7nm chips using older deep-ultraviolet (DUV) lithography; a surprise achievement, given it was cut off from the latest EUV tools. This showed China’s ability to innovate around Western restrictions when pressed. China is also investing in its own electronic design automation (EDA) software, semiconductor chemicals, and silicon wafer production; essentially, “aiming to control all parts of the supply chain” domestically. As one expert put it, “China is racing to achieve tech independence by any means, viewing it as a cornerstone of its strategic competition with the U.S.”.

Thus, the U.S.-China chip race has become a two-pronged contest: America and its allies strive to stay a couple of generations ahead in cutting-edge technology and manufacturing capacity, while denying China the ability to leapfrog, even as China throws massive resources into catching up. The U.S. still holds important advantages; it leads in many areas of chip design (think CPUs and GPUs by firms like Intel, NVIDIA, AMD) and in specialized chipmaking equipment, and it benefits from a network of trusted partners across Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and Europe. But those advantages will erode without sustained effort. Keeping the lead will require the U.S. not only to play defense (with export controls) but also to go on offense with relentless innovation.

Next-Generation Chips: Leaping Beyond Silicon

One way the U.S. plans to outpace China is by leapfrogging to the next era of semiconductor technology. Today’s chips mostly rely on silicon-based transistors, but as we approach the physical limits of silicon, researchers are exploring new materials and processes. The U.S. is heavily investing in what some call “post-silicon” semiconductors that could outperform standard silicon chips and be manufactured more securely onshore. A key proposal involves establishing advanced chip fabrication hubs in the U.S. (for example, in Texas and Arkansas) focused on novel semiconductor materials. These include exotic options like boron arsenide (BAs), silicon carbide (SiC), gallium nitride (GaN), bismuth triiodide (BiI₃), chromium sulfide bromide (CrSBr), and bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl). Each material has unique advantages: boron arsenide can dissipate heat far better than silicon (a boon for cooling chips), SiC and GaN are superb for high-power and high-frequency electronics (important for electric vehicles, 5G radars, etc.), and some bismuth and chromium-based compounds exhibit novel quantum properties that could be harnessed in future quantum computing or ultra-efficient memory.

By positioning itself at the forefront of these emerging materials, the U.S. hopes to “set the pace for the next generation of chips,” potentially leapfrogging incremental improvements that China might catch up to. A concerted five-year plan is already outlining how to develop and scale these technologies domestically, from lab research to pilot production lines to full-scale fabrication using 2D materials and other new substrates. One strategy paper cited in the report called these materials “game-changing platforms for next-generation semiconductors”. In other words, whichever country masters these breakthroughs first could command the high ground of tech for years to come.

Investing in new chip materials goes hand-in-hand with addressing supply chain vulnerabilities around them. Many exotic elements needed for advanced semiconductors are currently mined or processed almost entirely abroad, often in China. For example, China controls an estimated 98% of global gallium production and 80% of bismuth output (both are byproducts of base metal mining). Beijing vividly demonstrated this leverage in 2023 by imposing export controls on gallium and germanium (another niche semiconductor material), and hinting at further restrictions, as retaliation for U.S. chip sanctions. That move was a wake-up call, highlighting the urgency for the U.S. to secure its own supply of critical minerals tied to tech manufacturing. (We delve deeper into the rare earths and strategic minerals tussle in a later article.)

In response, a U.S. “domestic materials initiative” is being pursued to develop end-to-end supply chains at home or with allies. For instance, the U.S. has significant bromine reserves in Arkansas, and bromine is a key ingredient for the CrSBr semiconductor material. Plans are underway to tap those resources, and even to extract gallium from industrial waste streams of aluminum production in states like Texas (since gallium can be harvested from bauxite ore residues). The idea is to co-locate new material processing facilities alongside chip fabs, shortening supply lines and reducing the risk that overseas transport could be choked off in a crisis. These efforts underscore a broader approach: identify where the U.S. or friendly nations have untapped sources of critical materials and invest in bringing them online. It’s an expensive and complex endeavor, essentially trying to rebuild parts of the supply chain that were long ago offshored, but it directly targets one of the U.S.’s biggest strategic vulnerabilities vis-à-vis China.

The U.S. is also encouraging breakthroughs in manufacturing processes to regain its edge. A notable example: a U.S. company recently unveiled a novel X-ray lithography technique using compact particle accelerators to generate ultra-short wavelength X-rays. This can “print” chip features as fine as those made by ASML’s top EUV machines, but at a fraction of the cost. If scaled up, such homegrown lithography tools could reduce reliance on the Dutch-made EUV systems (which are not only costly and in limited supply, but also subject to geopolitical export restrictions). Integrating these new machines into future U.S. fabs could be a game-changer, enabling production of sub-5nm chips without needing to import the crown jewels of foreign equipment. U.S. policy is moving to vigorously support these kinds of “leap ahead” innovations, through funding, public-private partnerships, and government procurement, since they could redefine manufacturing and give the U.S. a durable advantage if successful.

Implications and Outlook

In summary, the U.S. strategy on semiconductors is twofold: (1) build up and expand domestic capability at the cutting edge (via investments like the CHIPS Act and fostering innovations in materials and tools), and (2) constrain China’s ability to obtain or produce the most advanced chips. The competition is intense and unlikely to slow. China is investing unprecedented sums and has shown resilience in the face of tech restrictions. But the U.S. and its allies still hold critical cards, including a more innovative private sector and deep pools of expertise through international partnerships.

For the global economy, this decoupling in the chip industry carries mixed effects. In the short term, costs could rise, building redundant supply chains means expensive investments, and consumers might see higher prices for electronics if cheaper production in China is curtailed. Over the longer term, however, a more geographically diversified chip supply could lead to a more stable market less prone to disruption. For countries caught in between, there may be pressure to choose sides, as two semiconductor ecosystems could emerge: one U.S.-led, one China-led. We’re already seeing early signs of this “tech bifurcation,” with Chinese tech firms designing more home-grown chips for domestic use, and U.S. firms avoiding Chinese suppliers in critical areas.

From a security perspective, America’s push to secure the semiconductor supply chain is about more than economics; it’s about ensuring the U.S. military maintains its technological edge. Advanced chips are indispensable for modern defense systems (AI, encryption, precision weapons, etc.). By securing a steady supply of the best chips, the “silicon shield” of the digital age, the U.S. intends to preserve the “qualitative edge to our military” that these technologies provide. This is seen as essential to retain overmatch in any future conflict, and to deter aggression by making sure U.S. forces are never technologically outgunned. In places like the Taiwan Strait, that qualitative military-technological superiority could be the factor that convinces adversaries not to risk war.

Looking ahead to 2026-2030, expect continued U.S. government focus on chips: more funding, tighter export rules, and deeper collaboration with allies (like Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea) to coordinate policies. China will likewise redouble efforts to break its dependence on Western tech, through huge investments, talent programs, and perhaps by exploiting any loopholes in export regimes. A key indicator to watch will be whether China can significantly advance its domestic chip manufacturing despite the controls. If SMIC or other Chinese fabs start mass-producing, say 5nm or 3nm chips without foreign tools, that would signal a major leap. Conversely, watch if U.S. companies successfully commercialize any of the post-silicon breakthroughs, which could change the game entirely.

For businesses and investors, the semiconductor tug-of-war means both challenges and opportunities. Chipmakers and equipment suppliers are reorienting supply chains and compliance practices. Allied countries like Taiwan and South Korea are being courted by the U.S. to build more capacity in America (and may get incentives to do so), even as they try not to alienate China, which is a huge market. Tech industries may see short-term disruptions, but in the process gain new markets (e.g., U.S. fab expansion is a boon for construction, tooling, and workforce development in the States). Venture capital is flowing into semiconductor startups in areas like new materials and manufacturing tech, spurred by this geopolitical urgency.

In the end, semiconductors exemplify the broader U.S.-China tech rivalry: it’s a competition to innovate faster while also locking in security for critical supply chains. The country that can produce the best chips reliably, at scale, will not only reap economic rewards but also ensure its military and industries run on the fastest, smartest brains available. For the U.S., maintaining that edge is worth the hefty price tag, because, as officials often remind, semiconductors truly are the backbone of the modern economy and the source of future power. The silicon race is on, and the world is watching closely.

Comments ()