Owning the Next Chip Paradigm: Bringing Advanced Fabs Back to America

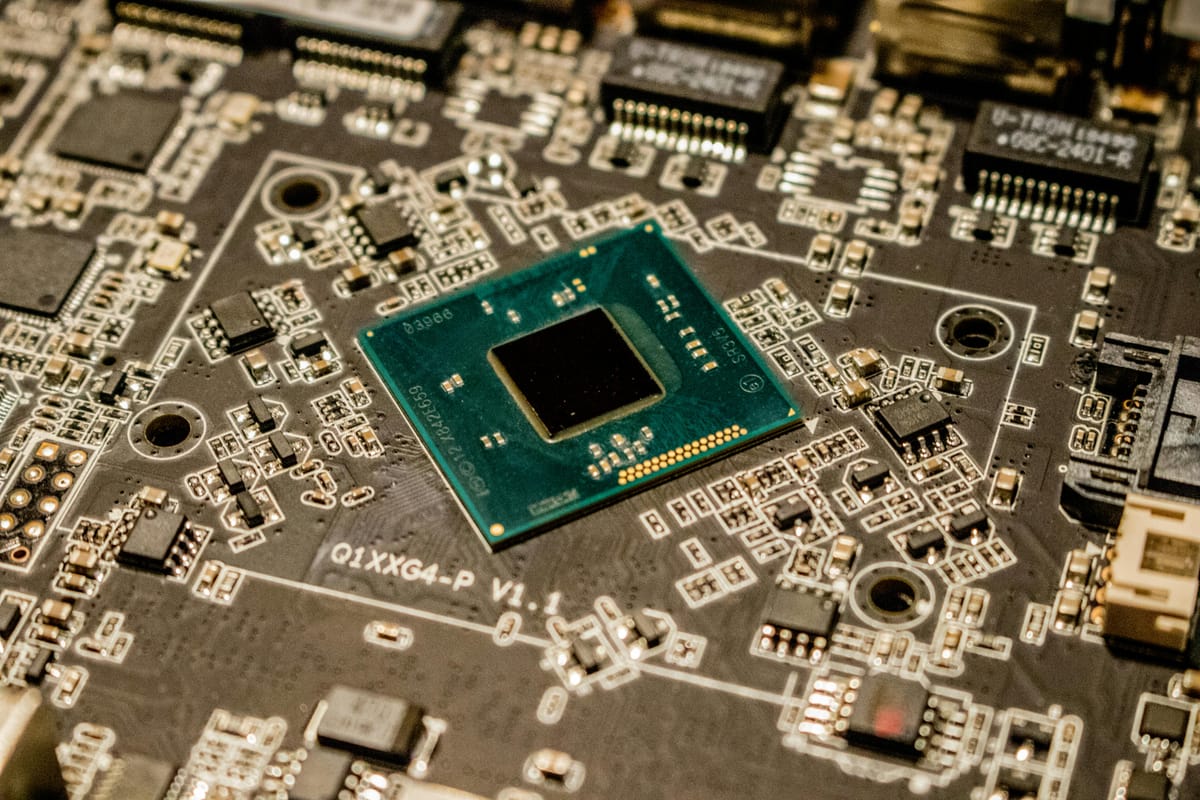

Today, over 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors are made in Taiwan, placing the “brains” of our defense systems, communications, and economy at the mercy of geopolitics.

The Risks of Offshore Chip Dependency

America’s reliance on overseas chip fabrication has become a glaring strategic vulnerability. Today, over 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors are made in Taiwan, placing the “brains” of our defense systems, communications, and economy at the mercy of geopolitics. This concentration is a single point of failure: a crisis in the Taiwan Strait or a trade embargo could sever U.S. access to high-end chips overnight, crippling both our economy and military capabilities. Recent history offers a stark warning; after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, sanctions cut off Moscow’s supply of advanced chips, forcing its defense industry to scavenge semiconductors from household appliances. The lesson is clear: technology power hinges on supply chain security, and no nation can lead if it cannot reliably produce the chips it needs.

Beyond national security, offshoring chips undermines economic competitiveness. The U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing has plummeted from 37% in 1990 to roughly 12% today. Virtually all cutting-edge logic chips (5 nm, 3 nm nodes) that power AI supercomputers and advanced weapons are fabricated abroad, eroding America’s strategic autonomy in innovation. A startling illustration came during the 2021-22 chip shortages: U.S. automakers lost billions in revenue when they couldn’t get critical microcontrollers, thanks to fragile overseas-centric supply chains. Such supply shocks exposed the economic costs of dependence and the folly of a just-in-time global supply for a foundational technology.

Policymakers have woken up to these risks. The 2022 CHIPS and Science Act injected $52 billion to revive domestic semiconductor manufacturing. This has already catalyzed a wave of new fab projects and is projected to create hundreds of thousands of jobs in America. Still, rivals are pouring even greater sums into their own chip sovereignty (China alone has earmarked well over $150 billion). In short, the race is on, and whoever leads in semiconductors will lead in the digital economy and defense. The United States cannot afford complacency. Sovereign capacity in advanced chips is now synonymous with economic power and military strength. Re-shoring fabs is not just industrial policy; it is about securing the supply of critical technology and maintaining technological supremacy.

Crucially, America’s goal should not simply be to replicate existing offshore foundries; it must leap ahead. The benchmark for success is not only matching TSMC or Samsung, but leapfrogging them with new technologies. Future supremacy will belong to those who master what comes after silicon. That is why the U.S. strategy is pivoting to the next frontier of materials and chips, rather than fighting yesterday’s node war.

Post-Silicon Materials: The Next Frontier

Maintaining Moore’s Law-era progress will require moving beyond silicon into new semiconductor materials that shatter current performance limits. Simply put, the next generation of game-changing chips will be built with post-silicon materials, and America’s leadership depends on having the fabs to produce them. These include ultra-high-performance compounds like boron arsenide (BAs), advanced van der Waals crystals (2D materials), and wide-bandgap semiconductors such as gallium nitride (GaN) and silicon carbide (SiC), as well as novel 2D quantum materials. Each offers unique advantages that silicon can no longer provide.

For example, boron arsenide boasts a record-high thermal conductivity (~1300 W/m·K) and excellent electron and hole mobility, enabling chips that run far cooler and faster than today’s silicon devices. Researchers note that heat dissipation is now as critical as transistor size for chip performance; by wicking heat efficiently, BAs-based processors could sustain higher power densities without throttling, a potential revolution in AI supercomputing. In fact, BAs have been called a potential “gamechanger” that could overcome thermal and electrical bottlenecks and “usher in an information revolution” in computing.

Likewise, wide-bandgap materials like GaN and SiC have already begun transforming power electronics and RF amplifiers, and they hold immense promise for high-frequency, high-voltage applications beyond silicon’s reach. SiC power switches, for instance, operate at much higher temperatures and efficiencies (vital for electric vehicles and aerospace), while GaN enables cutting-edge radar and 5G systems.

These wide-bandgap semiconductors are thus critical for interfacing quantum hardware with classical electronics and for next-gen communications. Meanwhile, an emerging class of 2D materials (often called van der Waals materials) offers exotic properties, some are intrinsic magnets, topological conductors, or superb dielectrics, that can be layered into devices atom-thin. For example, chromium sulfide bromide (CrSBr) is a 2D magnetic semiconductor that could enable spin-based quantum bits and novel memory devices. Bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl), to take another example, is a 2D crystal with a high dielectric constant (~3× higher than common 2D insulators) that could serve as superior gate insulation for next-gen transistors.

Each of these post-silicon materials offers distinct performance advantages, from ultra-high thermal conductivity to quantum magnetic properties, unlocking device applications beyond silicon’s limits. Harnessing them would position the U.S. at the forefront of the coming semiconductor paradigm shift.

Most importantly, these materials directly address the fundamental scaling and performance roadblocks faced by cutting-edge chips. As silicon transistors approach physical limits, stacking 2D materials and integrating new substrates is the way to keep improving density, speed, and energy efficiency. For AI processors, thermal removal is paramount; here, BAs can dissipate heat from AI accelerators or even quantum processors, allowing far denser integration of compute power. For quantum hardware, materials like CrSBr, BiI,₃ and BiOCl introduce functionalities (e.g,. stable magnetism, superior sensing, or integration of optical and quantum properties) that silicon cannot provide.

Post-silicon materials open up the path to faster, cooler, more specialized chips for AI and quantum technology, leaping beyond the plateauing capabilities of silicon alone. U.S. research institutions are already leaders in many of these areas; the strategic task now is moving these breakthroughs from lab to fab. By doing so, America has an opportunity to define the next semiconductor paradigm instead of merely catching up elsewhere.

Strategy for Securing U.S. Chip Leadership

Achieving this vision will require more than funds; it demands a strategic evolution of federal policy and industry approach. The CHIPS Act was a crucial first step, but future policy must explicitly nurture the next generation of materials and manufacturing. Below, we outline how U.S. policy should sharpen its focus to support domestic leadership in post-silicon semiconductors:

- Pilot Production Lines for New Materials: The U.S. needs dedicated pilot fabrication lines for non-silicon semiconductors to bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and high-volume manufacturing. Expanding CHIPS Act incentives beyond traditional silicon fabs, to include wide-bandgap and novel-material foundries, and funding pilot lines for materials like boron arsenide will accelerate this transition. Early pilot programs can work out the kinks of integrating 2D materials into process flows (e.g., transferring fragile films onto wafers, new etching techniques) and scale up crystal growth. By investing in pilot production now, the U.S. can ensure that breakthroughs in BAs, GaN, SiC, and other materials translate into working devices on reasonable timelines.

- Regional Manufacturing Hubs in Key States: Rather than concentrate solely in Silicon Valley, establish regional semiconductor hubs in areas with unique advantages; for example, North Texas and Northwest Arkansas. North Texas (Dallas-Fort Worth) boasts a robust semiconductor industry (home to multiple Texas Instruments fabs and a new Samsung facility) and leading research universities, while Arkansas offers top-ranked supply chain expertise and emerging wide-bandgap initiatives. By uniting Texas’s established chip ecosystem with Arkansas’s materials know-how (e.g., the new open-access SiC fab in Fayetteville), the U.S. can create a “Silicon Prairie” corridor of innovation. These hubs would host end-to-end production, from crystal growth and epitaxy to device fabrication and packaging, for post-silicon chips. Co-location of suppliers and fabs in such clusters shortens supply lines and streamlines logistics for sensitive materials (like arsine gas or corrosive bromine). Perhaps most critically, regional fabs tap into local talent pipelines: students from Texas and Arkansas universities can train in these facilities and become the skilled workforce that a next-gen semiconductor industry requires. The result is a distributed, resilient manufacturing base, not reliant on any one coast or region.

- Open-Access Lithography Innovation: Cutting-edge lithography is one of the biggest barriers to entry in advanced chipmaking; today, it is monopolized by a Dutch company’s EUV tools. The U.S. can democratize this by investing in open-access lithography technologies such as compact X-ray lithography developed domestically. For instance, a U.S. startup’s novel X-ray micro-lithography system uses compact particle accelerators to produce ultra-short-wavelength X-rays, achieving feature resolutions comparable to EUV at a fraction of the cost. Integrating these machines into new fabs would eliminate reliance on overseas EUV equipment, potentially slashing per-wafer patterning costs from around $100,000 to roughly $10,000 by decade’s end. Crucially, cheaper, more accessible lithography lowers the barrier for new materials; many post-silicon semiconductors won’t ship in the volumes of silicon, so they need affordable tooling to be viable. X-ray lithography can enable high-density GaN or SiC circuits without prohibitive expense. Federal support should establish shared-access lithography centers where startups, academia, and industry can all use these advanced tools for R&D, much like national lab user facilities. This not only underpins technical sovereignty (no waiting on foreign machine exports) but also spurs homegrown innovation in manufacturing processes.

- Secure Domestic Supply of Critical Inputs: Rebuilding the chip supply chain at home means securing the raw materials that next-gen semiconductors require. Many of these inputs, gallium and arsenic for III-V semiconductors, rare earths, specialty gases, are today dominated by foreign (often adversarial) sources. For example, China controls about 98% of global gallium and 80% of bismuth production, and has not hesitated to impose export controls on them. The U.S. must neutralize this leverage by developing domestic sources and stockpiles of critical elements. This could involve extracting gallium as a byproduct of domestic bauxite (aluminum) mining and tapping America’s substantial bromine reserves (Arkansas sits atop one of the world’s richest) to produce feedstocks for materials like CrSBr. Equally important is onshore refining and processing; for instance, building facilities to produce ultra-high-purity arsenic and boron compounds needed for BAs, so that U.S. fabs aren’t dependent on overseas chemical supply. Federal policy should extend the Defense Production Act or other incentives to encourage local mining, refining, and recycling of semiconductor-critical minerals. By securing these inputs at home, the U.S. closes off a potential chokepoint and ensures that no rival can strangle our advanced chip production by cutting off the materials pipeline. Supply chain resiliency isn’t glamorous, but it is as vital as the fabs themselves.

In concert, these policy measures form a blueprint for a secure, sovereign semiconductor ecosystem. They build on the momentum of the CHIPS Act but also correct its course: tilting it toward the future of chips, not just the present. Notably, this strategy calls for choosing new areas of focus rather than simply trying to duplicate TSMC’s model in America. It recognizes that U.S. strength can be in innovation and first-mover advantage on emerging technologies (quantum, 2D materials, etc.), supported by smart public-private coordination. By widening the scope of incentives, fostering regional centers of excellence, and removing bottlenecks in tooling and materials, Washington can catalyze a leapfrog of the current semiconductor paradigm.

The Strategic Payoff: Sovereignty and Technological Leadership

Ultimately, the goal of “bringing fabs back” is not nostalgia or protectionism; it is to secure America’s future as the leader in technology. Semiconductors are often called “the new oil” of the digital age, fueling every aspect of modern life. Losing control of oil in the 20th century would have been unthinkable for a superpower; likewise, losing control of chips means losing control of our future. Conversely, regaining control by mastering the next materials paradigm will secure both our prosperity and our security. A robust domestic chip ecosystem, grounded in post-silicon innovation, ensures that the United States can field the fastest AI systems, the most powerful supercomputers, and the most secure defense electronics without fear of supply cutoffs or hidden backdoors. It means the technological high ground, whether in quantum computing or autonomous weapons, will be held by America on American terms.

This vision is ambitious but attainable. The United States still possesses world-class research institutions, an unparalleled capacity for innovation, and now a clear recognition that semiconductors are a strategic priority. The payoff for acting decisively will be a U.S. chip sector that not only meets our own needs but produces “unequaled” chips that run faster, cooler, and more securely because they harness quantum materials and homegrown ingenuity. Rather than chasing incremental silicon improvements, we choose to leap ahead, combining 2D materials and quantum phenomena with advanced manufacturing to leapfrog Moore’s Law scaling and define the future of computing on our terms. This is how America can outcompete larger subsidized efforts: not by replicating TSMC, but by doing what TSMC can’t or won’t, pioneering the next paradigm.

At stake is more than industry leadership; it is the foundation of national power in the 21st century. A secure, sovereign chip supply chain means U.S. fighter jets, satellites, and critical infrastructure will never be compromised by foreign silicon. It means new industries and jobs blossoming at home, from Arkansas’s “Silicon Prairie” to Texas’s high-tech corridor. And it means the United States retains the ability to surprise the world with technological breakthroughs, as it has done in past generations. By investing in advanced fabs now, oriented around post-silicon materials, the U.S. positions itself to dominate emergent domains like AI and quantum computing in the years ahead. The message is one of confident resolve: America will not cede the semiconductor high ground. We will build and invent our way to a sovereign chip ecosystem, and in doing so, ensure that the coming era of computing is led by American innovation and safeguarded by American manufacturing. The choice is ours to make, and the time to act is now.

Comments ()